As a little girl growing up along the coast of West Africa, it was always a battle when it came to getting my hair done.

No volume of tears could soften the heart of a mum who was bent on making her only daughter look her best for Sunday church service. The routine, which always began with a gentle dialogue between mum and daughter and an offer of an “alewa” (candy) or two during the course of the braiding ordeal, almost always ended up with me wishing I was a boy, bald or both.

Today I have a 3-year-old daughter with much thicker, curlier, bushier (afro) hair than myself. I was at a loss a few months ago as to how to get her looking great in her Sunday best without the tears and sorrow. I asked myself, “Is this all we can do as African women? Just braid our hair to avoid the tangle?” After careful research, the unequivocal answer is yes.

So, where did braids come from? Africa of course, and they have been around for a pretty long time — 5000 years, originating from the OvaHimba in Namibia, according to Larry Sims, a renowned hairstylist.

The oldest image of a braid was first seen in Saqqara along the River Nile (Ancient Egypt). Braids have always had a cultural significance as one’s religion, tribe, age, marriage and social status could often be determined by the look, thickness and colour of the braid on their head. There are several well-known styles such as the cornrows, Fulani braids and goddess braids, but I am biased towards the Ghanaian braids, also known as fishbone, or banana braids (500BC) (Muhammad, n.d.), as it hails from my country of birth and it takes a relatively shorter amount of time to get done in comparison to the others.

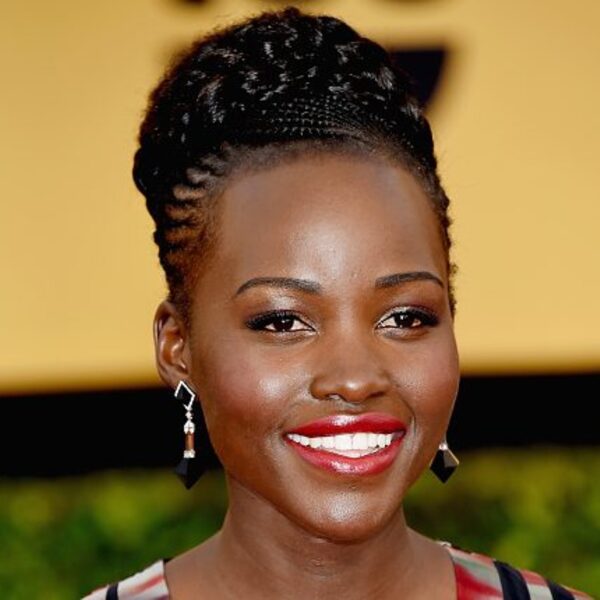

Over the years, there has been a metamorphosis from the traditional and historic hair braids to a more aesthetically modern braid. Hardly does any program, performance, or award show get celebrated without a celebrity rocking their expensive garments and sophisticated hairdos. The famous Gabrielle Union, Lupita Nyongo, Travie McCoy and most recently at the British Music Awards 2021, Jade Thirlwall (Little Mix), have showcased a type of fashion that tells a deep story from years ago.

Gabrielle Union: popsugar.co.uk

Lupita Nyongo: celebritynetworth.com

Little Mix: vulture.com

Travie McCoy: discogs.com

A. Fraser, Ph.D., (Assistant Professor, Brooklyn College) is of the notion that Black American hair culture cannot be understood without first educating ourselves on slavery and its impact on the African woman. History has it that the braided hair of women captured to be trafficked abroad were shaven, perhaps to rob them of their humanity, identity and culture. You would then think that the slave masters would carry this act through anytime the hair grew, but that was not the case. However, in a strange land where there was no ample time to sing folksongs around a bonfire, as men drank palm wine under the baobab tree and children listened to folktales that would give them sleepless nights, women in slavery had to give up their elaborate plaits and evolve simple, single plaits as a pragmatic means of wearing their hair, according to Lori L. Tharps (Associate Professor, Temple -University).

Dirshe writes that in spite of the torture, African women never lost their identity as they found ways to communicate with their hair. The number of plaited braids and style was an indication of the number of roads to be walked and a venue to meet to avoid some form of punishment or bondage. Tharps sums it up nicely in her quote, “People used braids as a map to their freedom.”

For a while after slavery, the average African woman chemicalised her hair, maybe to fit into the new civilised world, but also to break ties with anything that had the slightest smell of slavery. Until such a time when African American celebrities such as Floella Benjamin were bold enough to appear on stage with braids did the African American woman feel confident again to re-unite with her past and her culture. Having whites such as Bo Derek (in the movie 10) join the train cemented further the fact that it was alright to braid.

I began straightening my hair with chemicals after I graduated from high school because it was just what was done, in addition to the partying and smoking (if one had not already begun). With time, my hair thinned out and always looked dull. Living abroad in temperate regions only worsened the state of my hair as serious breakages became the order of a combing and detangling out session. After careful research, and thoughtfulness, I decided to go back to my roots in a “strange land,” i.e. keep my hair natural and keep it braided. This is because the weather is just not kind to the chemicalised African/African-American hair but it’s also the wisest thing to do in my bid to prevent my childhood wish of going bald from coming to pass.

There is a school of thought about braids contributing to Traction Alopecia (hair loss because of constant tugging on the hair and wearing the hair in a tight ponytail/ bun). The hair along the front and sides of the scalp usually gets affected the most. I do not doubt this as most braids look the neatest when all the loose strands along the hairline have been tucked firmly into the braid. So, to solve this problem, don’t braid the frontal hairs, change the hairstyle ever so often and lessen the use of chemicals in the hair. One should be good to go.

What we could do as African/African-American women is to use the good old natural shea butters, coconut oils and detangling combs to loosen the hair strands and to ease the pain of combing out our hair. When this process has been surmounted, braiding is the way to go. It is beautiful, elegant and a testament to cultures that have stood the test of time.